Highlights from the 2015 Social Security and Medicare Trustees Reports

July 23, 2015 - Download PDF Version

National Priorities Project breaks down what you need to know on the status of the Social Security and Medicare trust funds.

Yesterday the trustees of two key social insurance programs - Social Security and Medicare - released their annual reports projecting the future of the programs’ finances. What’s special about these trustees’ reports is that they consider the future of these programs 75 years into the future – something no other federal program does.

Social Security Is Not Going Broke

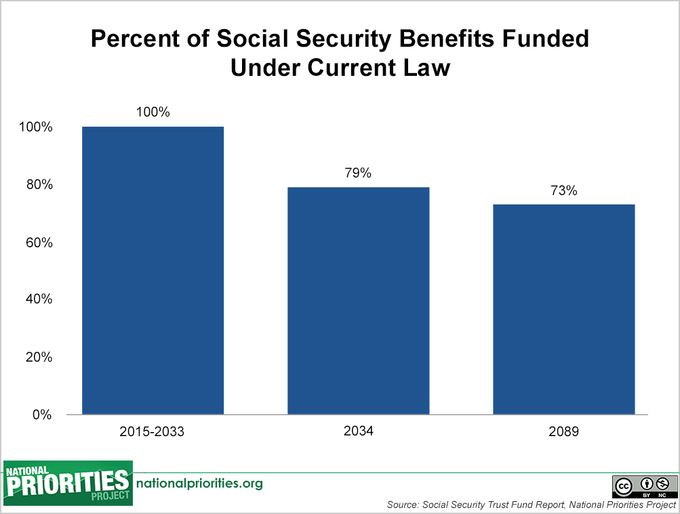

The Social Security Trustees Report breaks down trust funds for two separate portions of Social Security: the retirement and survivor’s benefits (OASI) and disability benefits (DI). Together, these two programs are fully funded until 2034, one year longer than the trustees put forward last year. What this means is that if Congress makes no changes to the Social Security program, revenues that come in from payroll taxes and other sources will be able to cover 100 percent of benefits until 2034 and 79 percent of benefits after that.

You may have heard that the disability insurance program’s trust fund becomes insolvent next year – in late 2016 – a figure unchanged from last year’s report. That’s because though the retirement and survivor’s program and disability program are often considered in conjunction, as noted above, they are actually two separate programs with their own trust funds. Once the disability trust fund is depleted, it will only be able to cover 81 percent of scheduled benefits. So, in order to prevent a 19 percent cut in disability benefits next year, Congress will likely need to temporarily reallocate some payroll tax revenue from the retirement and survivor’s program to the disability program, a step that’s been taken 11 times in the past.

In order to close Social Security’s overall long-term financing gap and ensure 100 percent of benefits could be paid well into the future, lawmakers must raise new revenues for Social Security, consider program cuts, or some combination of those two options. Simple adjustments to the program’s financing have received widespread support among Americans and could put the program on sound footing. Examples include raising the payroll tax gradually (currently 6.2 percent each for the employee and employer), or requiring higher income Americans to contribute more by subjecting more earnings to the payroll tax (currently only the first $118,500 in wages is taxed for Social Security).

Medicare Is Not Going Broke

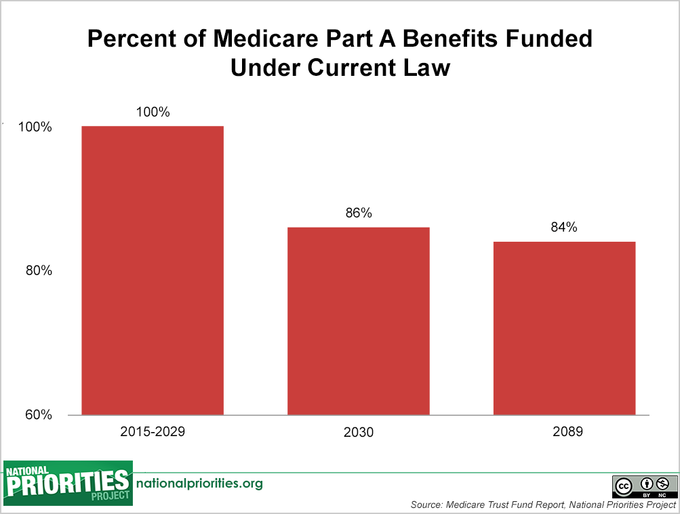

The Medicare Trustees Report found that Medicare’s hospital insurance trust fund (Part A) is fully solvent until 2030, the same projection the trustees put forward last year. If no changes are made to the program before 2030, Medicare Part A payroll taxes and other revenue would be able to cover 86 percent of payments in 2030 and would slowly decline after that. Parts B and D – medical insurance and prescription drugs, respectively – are sufficiently funded indefinitely because they’re funded with a combination of premiums and general tax revenue.

More good news is that the Affordable Care Act – a.k.a. Obamacare – seems to be contributing to the extended solvency of Medicare’s hospital insurance trust fund. Current projections give the fund an additional 13 years of solvency beyond the pre-Obamacare estimate.

In order to close Medicare’s hospital insurance trust fund’s long-term financing gap, Congress must enact program cuts, tax increases, or some combination of those. For example, Medicare’s deficit could be closed by increasing the payroll tax (currently 1.45 each for employees and employers) to 1.9 percent.