You Ask, We Answer: Are Tax Breaks Government Spending?

By

Becky Sweger

Posted:

|

Budget Process

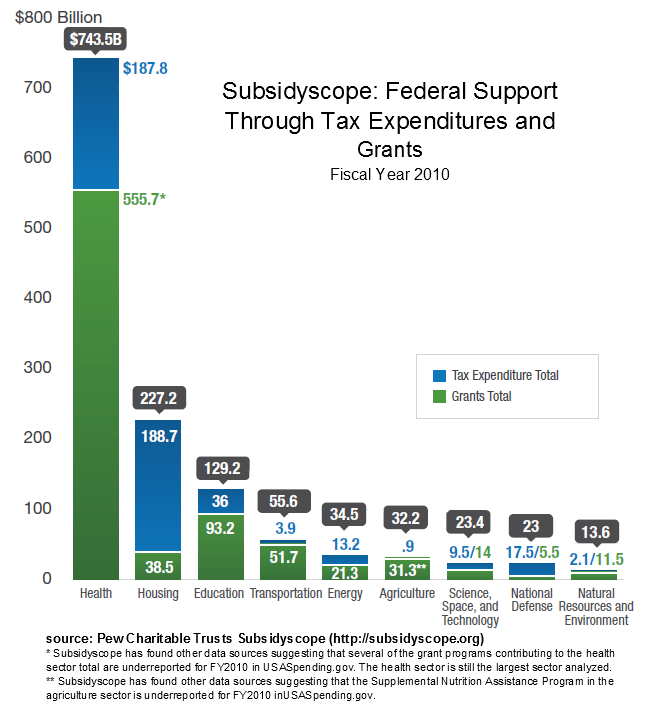

In last month’s The Untold Story of Deficits in Washington, Mattea Kramer wrote that tax credits, deductions, and exclusions in the individual and corporate income tax codes cost the U.S. federal government $1.3 trillion in tax revenue. When these tax expenditures are added to grant money, we get a more complete picture of federal spending:

"But wait," wrote several of you, "taking less of our money is not the same thing as spending."

Think of it this way. Each year, your individual income tax bill to the federal government comes due. The amount you owe depends on how much money you made and the current tax rates—it’s all there in those handy tables at the back of the IRS 1040 booklet.

Because of a host of government mandates, however, most people don’t pay the full amount shown in that table. Congress promotes goals like home ownership, healthcare, and education by passing laws that reduce your tax bill if you pay interest on a mortgage, for example, or have medical or health-related expenses.

We call these credits, deductions, and exclusions spending because the government giving you a discount on your tax bill is effectively the same thing as the government writing you a check—both scenarios result in the Treasury having less money.

Unlike “regular” spending such as grants, tax credits and deductions aren’t reauthorized each year by Congress, so they’re less visible. But an honest discussion about federal spending has to include all types of federal subsidies, not just the check-writing kind.

For more information about government subsidies, including tax expenditures, see the Pew Charitable Trusts’ Subsidyscope project.