How $9.3 Billion Funds Coronavirus Outbreaks in Federal Prisons

By

Sidney Miralao

Posted:

|

Health Care,

Military & Security

Since the first alarms were raised in February about the COVID-19 pandemic arriving in the U.S., healthcare experts and prison reform advocates alike began raising concerns about how dangerous the virus would become in a system holding 2.3 million people on any given day.

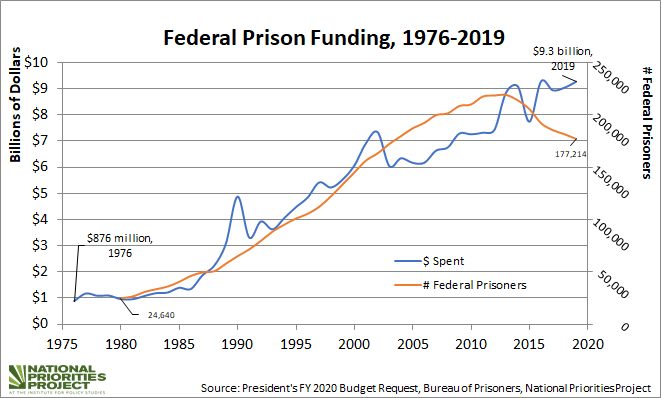

The United States has the largest prison population in the world; the federal prison system holds nearly 165,000 people, which is less than 10% of the total prison population. Millions more reside in state and local facilities. Even with its comparatively smaller operation though, the federal prison system spent $9.3 billion in 2019.

Healthcare is the Bureau of Prison’s second greatest costs following staffing expenses, and medical care, drug treatment, and psychological care totaled to about $1.34 billion in 2016. However, it is well-documented how sparse healthcare services really are in these aging facilities, to say the least, so it is easy to conclude that prisons are ill-equipped to handle the dangers a global pandemic presents for those who live and work in prisons.

Mass incarceration is thus a “uniquely American risk” when it comes to trying to slow the spread of the virus. As of June 23, The Marshall Project reports there are around 48,764 confirmed cases of the virus in jails and prisons, with 12 of the 15 largest outbreaks of the virus occurring at correctional facilities.

Much of this has to do with the fact that jails and prisons are overcrowded and understaffed; with populations of up to 2,000 at federal prison facilities, social distancing is practically impossible. Unsanitary facilities operating at full capacity, along with the lack of testing, failure to distribute PPE, or even basic amenities like soap or hand sanitizer, and the fact that there are around 35,000 employees moving in and out of these facilities everyday, makes the spread of the virus in prisons and surrounding communities all the more likely.

We must also acknowledge how the prison population is much more vulnerable to the virus than the general population; nearly 20% of incarcerated people in the federal prison system are aged 50 or older, and there is an overrepresentation of people with physical or cognitive disabilities and chronic illnesses in prisons, who are more often than not deprived of necessary medical care.

This all really begs the question: why are we spending billions on a system set up only to amplify harm, especially in the context of a global public health crisis? As the calls for defunding police gain momentum around the country, we should consider how these arguments can be extended to the justice system and prisons.

Although the CARES Act provided the BOP an additional $100 million in emergency funding to respond to COVID-19 and expanded the use of home confinement, the federal government has yet to take action on the one thing the United Nations, health experts, and activists agree could mitigate further spread of the virus: mass decarceration.

Many states have begun the process of reopening despite the massive resurgence in infections across the U.S., which reported 44,000 new cases last Friday. Meanwhile, prisons and jails remain hotspots of the pandemic where infection rates are rising sharply. Until the United States commits to truly de-densifying prisons and reconsidering the forces that lead to mass incarceration, it cannot pretend that the pandemic will fade away any time soon.