FPIF commentator Walden Bello is the co-chairperson of the Board of the Bangkok-based Focus on the Global South and the International Adjunct Professor of Sociology at the State University of New York at Binghamton. This is the first of two articles on the legacy of Osama bin Laden.

Osama's Ghost: The Economics of Overextension

By

Guest Blogger

Posted:

|

Military & Security

By Walden Bello, originally published in Foreign Policy in Focus.

The first part of our assessment of Washington’s 20 years of continuous war in the Middle East focused on its military and political costs. This part will discuss the economic consequences of this misadventure. Imperial overstretch, as historian Paul Kennedy points out, is not only a result of a mismatch between military goals and military resources but of the increasing inability of the economy to generate the resources to support a political and military strategy that might have seemed manageable when it began.

The Trillion Dollar War

By the end of the Bush administration, the United States had spent nearly $3 trillion on the war in Afghanistan and Iraq, according to the estimates of Linda Bilmes and Joseph Stiglitz. This was staggering. But as the wars were being pursued, the American public did not realize their true cost because the Bush administration chose to pay for the war via yearly emergency supplemental appropriations, which amounted, as analyst Doug Bandow put it, to a “pay-as-you-go” system.

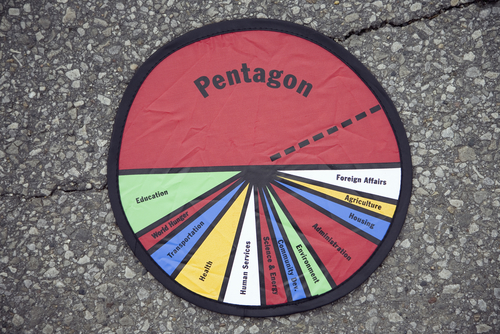

Bush II avoided raising taxes to fund his wars since that was a surefire way of eliciting public opposition to these adventures. Indeed, he cut taxes on the rich. The preferred course of action was massive borrowing, a course that eventually added some $1 trillion to the national debt. Afghanistan and Iraq were, in turn, part of a massive defense buildup, funded by debt, to achieve the unchallengeable hegemonic position the neoconservatives sought. Bush II’s defense budget averaged $601 billion per year, compared to Pentagon spending of $458 billion per year throughout the Cold War (1948-1990).

Americans began to feel the costs of the war toward the end of the decade as the economy weakened, then spiraled into recession following the global financial crisis in 2008, bringing to the surface the hard choices that had to be made in a condition of severe indebtedness. As Linda Bilmes and Joseph Stiglitz warned in 2008:

The long-term burden of paying for the conflicts will curtail the country’s ability to tackle other urgent problems…Our vast and growing indebtedness inevitably makes it harder to afford new health-care plans, make large-scale repairs to crumbling roads and bridges, or build better-equipped schools. Already, the escalating cost of the wars has crowded out spending on virtually all other discretionary federal programs, including the National Institutes of Health, the Food and Drug Administration, the Environmental Protection Agency, and federal aid to states and cities, all of which have been scaled back significantly since the invasion of Iraq.

But it was under the succeeding Obama administration that the full impact of the poisonous economic legacy of the Bush wars was felt. Rising concern over the massive debt—of which war-related debt was a central component–-became a severe constraint in crafting a large enough stimulus program to enable the United States to surmount the recession triggered by the 2008 Wall Street implosion. The $787 billion stimulus Obama got through Congress might have prevented the economic crisis from getting worse, but it was not enough to reignite the economy to overcome the 9 percent-plus unemployment that settled over the country during most of Obama’s reign. Even as Obama batted down pleas by some of his advisers to raise the stimulus to $1.5 trillion in order “to end the depression now,” as Paul Krugman put it, he raised military spending. While Bush II’s defense budgets averaged $601 billion per year, Obama spent an average of $687 billion annually between 2009 and 2014, provoking one libertarian analyst to comment acidly: “President Obama, who was elected during an economic crisis, will leave office having approved more military spending than any presidential administration in the nuclear era. Not too bad for a president who is often accused of trying to gut the military.”

Disaffection with costly interventionist wars played a central role in getting Trump elected in 2016. By then, even as thousands of U.S. forces remained embedded throughout the Middle East and Southwest Asia engaged in the interminable War on Terror, the economic base to sustain Washington’s costly military adventures was being eroded. Deindustrialization set in as U.S. transnational corporations shifted their manufacturing operations to China. Finance became the preferred investment area owing to high profits derived from it, leading to speculation becoming the driving force of the economy, and ending with the great Wall Street collapse of 2008.

America Pinned Down as China Takes Off

The logic of financialization was ruining the U.S. economy even as rapid industrialization— with massive support from American TNCs transferring industrial processes to China to take advantage of labor that was 2.9 percent the cost of U.S. labor—was giving China’s economy a solid foundation and spurring its global expansion, as it supplied manufactured goods to the United States and other markets while its need for raw material and food stimulated the economies of the global South. Before the COVID-19 pandemic, in 2019, China had become not only the world’s second biggest economy. It had become the center of global capital accumulation or, in the popular image, the “locomotive of the world economy,” accounting for 28 percent of all growth worldwide in the five years from 2013 to 2018, more than twice the share of the United States, according to the International Monetary Fund.

One key reason China prospered was because of its low spending on defense during its decades of industrialization, a strategy that then-Chinese President Hu Jintao described as China’s “peaceful rise” in the early 2000s. Although the 2002 Defense Department Strategy Paper identified China as the main U.S. strategic competitor, the Bush II administration’s desire to get China behind its war on terror as an ally post 9/11 allayed Beijing’s fears of U.S. military power being directed at it.

Neither was China overly worried about U.S. military power under Obama to push it to significantly raise military spending despite the vaunted “Pivot to Asia” of America’s strategic posture. Beijing knew that the United States was far too enmeshed with China as a production site for its TNCs, a market for American high technology, and a source of cheap manufactured goods for American consumers for Washington to carry out a disruptive military containment strategy.

The strategy of China’s “peaceful rise,” which relegates military upgrading far behind economic modernization as a priority, has continued to reign up until the Xi Jinping era, though more militant rhetoric now accompanies China’s responses to U.S. initiatives. Even now China has made little effort to close the spending gap with the Pentagon, with the latter devoting more than three times more than Beijing spends on defense. Reflecting this relatively relaxed view when it comes to military modernization, Xi told the Nineteenth Party Congress in 2017 that China will not have a “world class military” –meaning one that is at par with the United States–until 2049.

Instead of being preoccupied with building up its military might, Beijing has focused on opening markets in Africa and Latin America and becoming a source of billions of dollars of development aid, even as bilateral U.S. economic aid has been neglected in favor of ever increasing military assistance and subsidized weapons sales to old allies like Israel, Egypt, and Saudi Arabia. The launching of the Beijing-sponsored Asian Infrastructure Development Bank in 2014 saw even traditional U.S. allies in Europe queue up to become partners. More governments from both the global South and the global North signed up when Beijing rolled out the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) that proposed to spend over $4 trillion dollars for infrastructure projects to connect the Eurasian landmass, Africa, and Latin America.

When Trump came to power in 2017 and promoted the doctrine of “America First,” Xi Jinping was quick to go to Davos to proclaim China’s leadership of the globalization process. China was winning the diplomatic game even as Trump alienated old allies like Germany by carping that they were not carrying their fair share of the burden of defending them. For Trump, the answer to China was not to compete with Beijing in the diplomatic Olympics but to punish it economically with trade sanctions and an aggressive effort to change its state-led capitalist mode of production. Yet when it came to relating this aggressive economic strategy to the continuing priority of the War on Terror focused on the Middle East in the U.S. military agenda, incoherence ruled, as it did in most of Trump’s foreign policy initiatives. America First or not, the War on Terror lobby was determined not to disengage from the Middle East.

With the new Biden administration, there has been hope in liberal circles that America’s economic priorities are being reordered. Many of the thrusts of the $6 trillion budget for FY 2021-2022 show promise in terms of addressing the country’s dilapidated physical infrastructure and a social infrastructure marked by growing poverty and gross inequality. There is one area, however, that is more of the same: defense. Reflecting Biden’s reluctance to displease the generals, the budget raises the resources devoted to the military from $740 billion during Trump’s last year in office to $753 billion. A significant portion of the budget will go to supporting the military infrastructure that the Pentagon has built up over the last 20 years in waging its War on Terror in the Middle East and elsewhere.

Osama’s Ghost

Twenty years after 9/11, the United States may still be the premier global power, but it is a much diminished one. Osama bin Laden’s outrageous action did not adhere to the Guevarist playbook of igniting a thousand Islamic fires, but it ended up achieving his strategic aim of bringing about U.S. overextension by providing the opportunity for Bush and the neoconservatives to try to realize their equally implausible dream of achieving unchallengeable military supremacy globally. Once committed, U.S. troops were infernally difficult to withdraw, as Obama and Trump found out as they saw their priorities run up against a powerful military and political lobby with an interest in a continued U.S. presence in a region that has been a graveyard of empires.

Robert Gates served as secretary of defense to both George W. Bush and Barack Obama. He resigned shortly after Osama bin Laden was killed in 2011. In a speech to West Point cadets in September 2011, Gates paid a back-handed compliment to Osama, without of course mentioning him, while issuing a stinging criticism of the American leaders that took his bait and drove the United States to the Middle East quagmire from which it still has to extricate itself: “In my opinion, any future defense secretary who advises the president to again send a big American land army into Asia or into the Middle East or Africa should ‘have his head examined,’ as General MacArthur so delicately put it.”

Twenty years since 9/11 and the invasion of Afghanistan, the United States is still haunted by Osama’s ghost.

--