United States National Debt

As of December 15, 2015, the U.S. is $18.8 trillion in debt.

What Is the Debt Ceiling?

The debt ceiling is the legal limit set by Congress on the total amount that the U.S. Treasury can borrow. If the level of federal debt hits the debt ceiling, the government cannot legally borrow additional funds until Congress raises the debt ceiling.

Congress has the legal authority to raise the debt ceiling as needed. Doing so does not authorize new spending, but rather allows the Treasury to pay the bills for spending that has already been authorized by Congress.

Why Is There a Debt Ceiling?

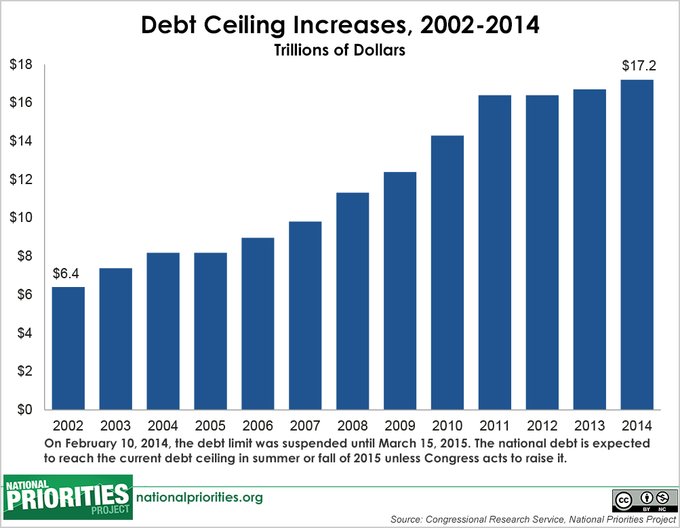

The debt ceiling evolved from restrictions that Congress placed on federal debt from nearly the founding of the country. Legislation that laid the groundwork for the current debt ceiling was passed in 1917, and the first overall debt ceiling was passed in 1939. Since then, the debt ceiling has been raised more than 100 times, including more than a dozen times since 2000.

In many years, the decision by Congress to raise the debt ceiling has not been controversial. Since 2011, however, due to political partisanship as well as debates about the size of the federal budget and deficit spending, the debt ceiling has become a highly contentious issue.

The Current Debt Ceiling

In February of 2014, Congress voted to suspend the debt ceiling, saving the U.S. the risk of either defaulting on its loan payments or drastically, and likely haphazardly, cutting federal spending.

The current debt ceiling suspension expired on March 15, 2015, but the government will likely be able to continue operating through fall using some previously identified “extraordinary measures” to allow additional borrowing. It’s unclear exactly when the money will run out, but sooner or later, lawmakers will have to deal with it.

Some members of Congress have pledged to allow the federal government to default on its debt payments rather than raise the debt ceiling. Yet, not raising the debt ceiling can have serious long-term consequences like rising interest rates, a suffering stock market, and less overall economic activity (meaning fewer jobs).