Talking About Military Spending and the Pentagon Budget – Fiscal Year 2013 (And Beyond)

Feb. 8, 2012 - Download PDF Version

CONTACT:

|

Christopher Hellman |

Carl Conetta |

Q: There’s been a lot of conflicting reports in the media in recent months about possible cuts to Pentagon spending. What are the numbers, and what’s really going on?

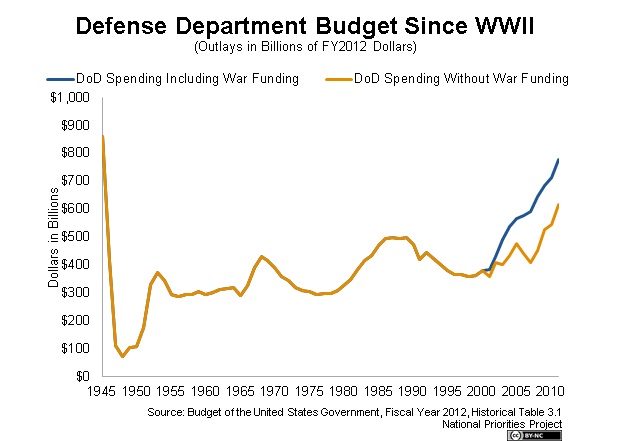

A: The new Pentagon budget plan released on Jan. 26 sets the Defense Department’s annual “base” budget for Fiscal Year 2013 at $525 billion – 46 percent above the 1998 level. Adjusted for inflation the change from 2012 to 2013 will be a reduction of 3.2 percent. In addition the base budget jumped 55 percent after inflation between 1998 and 2010. These figures do not include war costs or the nuclear weapons activities of the Department of Energy.

As the chart below shows, current defense spending levels – even without funding for the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan – are higher than at any time since World War II when adjusted for inflation.

Q: Recently the Pentagon announced its new strategic plan which will guide how it trims $259 billion from its budget over the next five years. What’s in it?

A: On Jan. 5 Defense Secretary Leon Panetta and Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff General Martin E. Dempsey – joined by President Obama in a rare visit to the Pentagon – rolled out the military’s new strategic plan.

Secretary Panetta and General Dempsey’s briefing was short on detail, but here are the basics:

- The military of the future will be smaller, but more agile.

- Post-Iraq and Afghanistan, the size of the Army and the Marine Corps – their “end-strengths” – will be reduced.

- The military will rely less on stationing troops at forward bases – there will be a draw down of U.S. forces in Europe, for example.

- The military will continue to shift its focus towards the Asia Pacific region, in part in response to China’s growing economic and military power, while maintaining a robust presence in the Middle East.

On Jan. 26 Secretary Panetta and Gen. Dempsey released some details of the upcoming fiscal year 2013 budget request. It includes provisions to remove two Army brigades from Europe and reduce overall Army and Marine Corps end-strengths by roughly 100,000. Nonetheless, the Marine Corps and the Army will still be larger than they were prior to Sept. 11, 2001.

Q: Does a smaller military mean it will be less expensive?

A: Not according to the Pentagon and the White House. Defense Secretary Panetta is scrambling to find an estimated $487 billion in cuts over the next decade, and says that anything further would be “disastrous.” Meanwhile, President Obama told a Jan. 5, 2012 Pentagon briefing that "over the next 10 years, the growth in the defense budget will slow, but the fact of the matter is this – it will still grow…”

Q: Won’t reductions in military spending mean fewer jobs?

A: Studies have shown that compared to other areas of federal investment, military spending is a poor source of job creation. According to the Political Economy Research Institute (PERI), each $1 billion invested in clean energy technology generated 50 percent more jobs than the same amount of spending on the military. Investing in health care created 54 percent more jobs, while $1 billion spent on education resulted in 138 percent more jobs. Or to put it another way, if federal investment in the military creates fewer jobs than other federal spending, then cutting the military will cost fewer jobs than cuts to other programs.

For more on jobs and military spending, see PDA’s "The Pentagon Budget and Jobs: How Does Defense Spending Rate for Job Creation?"

Q: What is Congress likely to do in the face of Pentagon efforts to reduce defense spending?

A: Some members of Congress are willing to put defense spending “on the table,” particularly in the name of deficit reduction. Members will continue, however, to resist cuts to their pet projects. Cutting weapons programs has never been easy on Capitol Hill. That won’t change.

SEQUESTRATION

The Budget Control Act passed last summer created the “super committee” of 12 senators and representatives whose task it was to come up with a plan that would generate at least $1.2 trillion in deficit reduction over ten years. If they failed to reach an agreement or if Congress failed to enact the committee’s recommendations it would trigger automatic across-the-board spending cuts to reach the $1.2 trillion threshold – a process known as “sequestration.” In order to avoid sequestration Congress has until December 2012 to reduce projected deficits by $1.2 trillion.

Congress and the White House included sequestration in the process as an incentive to reach a deficit reduction agreement. They believed that the indiscriminate cuts which would occur under sequestration would be so drastic that no one would want them to happen. Sequestration was intended to be a “gun to the head” of Congress that would propel it to act, and not a desirable outcome of the process.

Yet the super committee failed to issue a recommendation and Congress has so far failed to reduce the deficit by the required amount on its own initiative. Thus the possibility of sequestration now looms. As it stands, beginning on Jan. 1, 2013, automatic spending cuts equaling $1.2 trillion over 10 years will be split 50/50 between defense discretionary and non-defense discretionary programs, with each expected to generate roughly $55 billion in savings annually.

It has been widely reported that war-related funding (also known as “Overseas Contingency Operations”) is exempted from sequestration. The Office of Management and Budget (OMB) has yet to make a final determination on the matter, and is expected to do so in early February.

Q: Given how drastic the proposed cuts to defense and domestic discretionary programs might be, will sequestration happen?

A: There is a growing belief, from both supporters of domestic programs and the Pentagon that the cuts mandated by sequestration are too deep and that the arbitrary nature of across the board cuts – where all programs are affected equally – means that funding cuts won’t be prioritized between those that shouldn’t be cut and those that should. It appears increasingly likely that sequestration will be avoided in some way – be it delayed, dodged or revoked. Congress can also halt sequestration by meeting the spending reduction goals set by the Budget Control Act.

It is important to note that the federal government has faced the threat of sequestration a number of times in the past, and that Congress has avoided these cuts or allowed only small reductions in discretionary spending as a result.

Q: But what if Congress doesn’t act and the automatic cuts do occur?

A: As the recommendations of the Sustainable Defense Task Force – a group of national security experts who have outlined ways to cut nearly $1 trillion in military spending over a decade – and other analyses show, the Pentagon can absorb the cuts mandated by sequestration (and more) without negatively impacting U.S. national security. Domestic discretionary programs would not be so lucky. Here’s why:

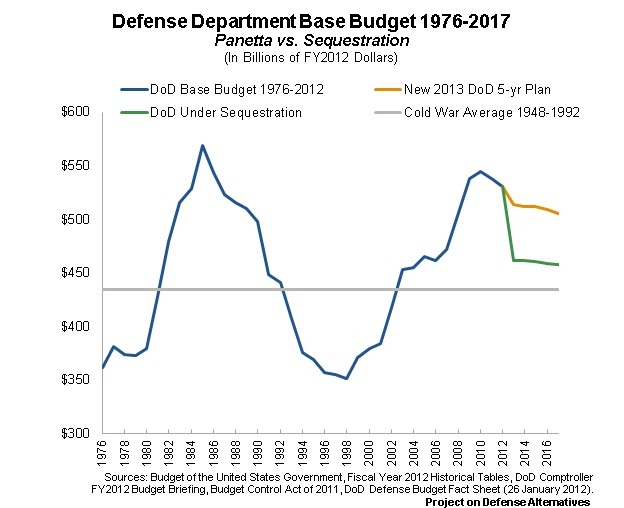

- Adjusted for inflation, military spending has grown 48 percent over the last ten years (FY2001-2011), not including war funding. This is more than enough to absorb the planned $487 billion cuts over the next ten years, plus any additional cuts that would result from sequestration.

- Pentagon spending cuts will be proportionally smaller than those for non-defense discretionary programs – such as education, energy research and job training – which represent a smaller percentage of total discretionary spending than the military and have not enjoyed the rapid funding growth the Pentagon has experienced over the last ten years. Non-defense discretionary spending has grown 32 percent over the last decade.

Q: Is it true that Pentagon supporters are trying to prevent sequestration cuts to defense?

A: Yes, a number of members of Congress have indicated that they want to exempt the Pentagon from automatic cuts. For example, Senator John McCain (R-AZ) and several other Republican senators have introduced legislation that would prevent sequestration cuts to both defense and non-defense spending by freezing federal employee pay and reducing the number of new federal employees. Similar legislation has also been introduced in the House of Representatives.

THE FUTURE OF U.S. MILITARY SPENDING

Q: Defense Secretary Panetta has said any additional cuts beyond those already planned would be “disastrous.” Can we cut military spending in ways that enhance our national security?

A: Analysis like that done by the Sustainable Defense Task Force show ways to achieve significant savings and keep our nation secure. Even the Pentagon’s proposed cuts and additional reductions from sequestration would not erase the significant growth the Pentagon’s annual (non-war) budget has experienced since 1998.

Even opponents of reducing Pentagon spending admit that they can live with the Administration’s proposed $487 billion in cuts from projected spending levels. House Armed Services Committee Chairman Howard “Buck” McKeon (R-CA) stated when he voted for the Budget Control Act that “I will support this proposal with deep reservations.” Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff Gen. Martin Dempsey has said that the Pentagon has not been “victimized” as part of efforts to reduce the federal debt, and that "...it makes no sense for us as a nation to have an extraordinarily capable military instrument of power if we are economically disadvantaged around the world. So we’ve got to rebalance ourselves..."

In a recent interview former Defense Secretary Robert Gates said the idea that the U.S. military is in decline is “ridiculous.”

Meanwhile, Reps. Peter Welch (D-VT) and George Miller (D-CA) have sent a letter to President Obama signed by 127 House Democrats supporting his threatened veto of legislation that would block defense funding cuts under sequestration without replacing them with equal savings elsewhere in the federal budget. Further, there are a number of elected officials who think the Pentagon’s proposals don’t go far enough. Rep. Barbara Lee (D-CA), along with Rep. Barney Frank (D-MA), Rep. Rush D. Holt (D-NJ), and Rep. Lynn Woolsey (D-CA), recently sent a letter to the president urging the administration to consider a “fundamental rethinking of our national security strategy,” as well as a “substantial reduction in military spending."

Q: Are there any problems with cutting the Pentagon’s budget?

A: Secretary Panetta has argued that across-the-board cuts mandated by the sequestration may force him to cut certain programs more than is practical and not cut others as much as he would like. He’s requesting the authority to distribute any additional cuts within the Pentagon’s overall base budget as long as it yields the same reduction. Likewise, an immediate cut in fiscal year 2013 of $55 billion may be too much to absorb, given the nature of the annual budget process. A phased-in and gradual reduction of $1 trillion in defense spending over the next decade may be a more practical alternative.

Current law dating from the 1980’s allows the president to exempt personnel accounts which health care, retirement benefits, and compensation from automatic cuts. However, commensurate reductions to other Pentagon accounts would be required.

Q: What is it that makes us truly strong as a nation?

A: Gen. Dempsey has spoken about the "four instruments of national power...diplomatic, information, military, and economic." His predecessor, former Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff Adm. Michael Mullen called the national debt "the most significant threat to our national security." What these military leaders acknowledge is that our national strength flows from our economic strength. Having a ready military alone is not enough to keep us secure. And creating a leaner, more sustainable and cost-effective military actually enhances our national security and economic strength.