Government is Giving Way Too Much Money to the Wrong People

NPP Pressroom

Wall Street Cheat Sheet

Dan Ritter

08/27/2014

One of the golden rules in economics is that you shouldn’t spend more than you make. If you do — if your outlays are larger than your inlays for any given period — then you are running a deficit. Repeat deficits turn into debt, and while there is such a thing as prudent use of credit, Americans generally seem unable to come to terms with this rule. At nearly every level, from households to the federal government, we are spending more than we earn, making debt one of the defining characteristics of the U.S. economy.

The problem at the household level is staggering. Americans held just over $11.2 trillion in debt at the beginning of 2013, but total household debt levels have actually been declining since about 2008. Between the third quarter of 2008, when total household debt peaked at $12.68 trillion, and the second quarter of 2013, household debt fell $1.53 billion, or about 12 percent. As a share of GDP, household debt fell from 85 percent to 67 percent over the same period. This was primarily due to a a reduction in mortgage debt, from $9.99 trillion to $8.38 trillion, which was partially offset by an increase in student loan debt, from $610 billion to about $1 trillion.

The problem at the federal level is also staggering. Gross U.S. public debt was $16.72 trillion in 2013 and debt levels are actually getting worse. Gross public debt is up 67 percent since 2008 and up 420 percent since 1990. Moreover, despite recent reductions to the deficit, public debt is expected to continue increasing in each year of the foreseeable future, projected to climb nearly 30 percent to $21.67 trillion by 2019.

For a different angle on the issue, public debt was about 53.6 percent of GDP in 1990, 67.9 percent of GDP in 2008, and 99.5 percent of GDP in 2013. By 2019, public debt is anticipated to be 97.6 percent of GDP due to a shrinking deficit and ongoing economic growth.

Although the projections suggest that we will break out of the insane and unsustainable trend of ever-increasing debt, the reality of the situation is still incredibly grim. The government is just spending way too much money.

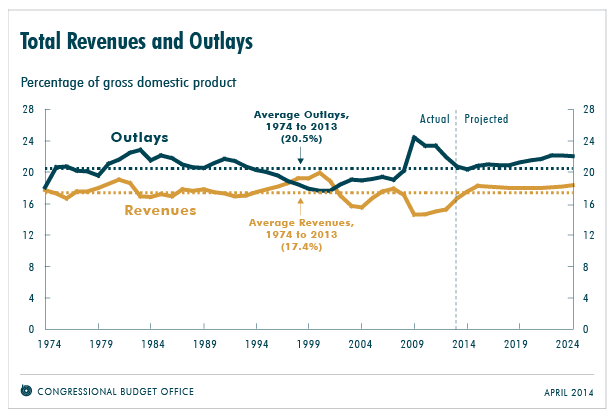

Granted, the government is spending less money now than it was a few years ago. In fiscal year 2013, the U.S. federal government spent a grand total of $3.45 trillion, accounting for a relatively trim 20.8 percent of gross domestic product. This compares against spending of $3.54 trillion, or 22 percent of GDP, in 2012, and spending of $3.6 trillion, or 23.4 percent of GDP, in 2011. Over the past 40 years, government spending has averaged 20.4 percent of GDP.

But even though we are spending less, we still haven’t figured out how to pay for everything. The government raised $2.77 trillion in 2013, about 16.7 percent of GDP. Revenues have increased each year since 2008, but total receipts are still below the long-term average of 17.4 percent of GDP. And although the 2013 deficit of $680 billion, 4.1 percent of GDP, was the lowest since 2009, it’s still larger than the 3.1 percent long-term average. While the deficit is projected to shrink over the next few years, it’s expected to expand back above the long-term average in 2019.

Here’s the problem: Government spending, which increased dramatically in response to the financial crisis, was cut about down to size during the recent rounds of budget negotiations, while revenues, which decreased dramatically during the Great Recession, have nearly recovered. However, government revenues are expected to flatline in the foreseeable future, while spending is expected to continue to rise. This is all assuming current laws don’t change.

Source: Congressional Budget Office

So the big question that people have been throwing around is: What do we do about it? Chronic deficits are simply unsustainable, and debt is a drag on the economy. The government spent $251 billion simply servicing its debt in 2013, and while much of this debt is held by the American public and by American corporations, much of it is also held by foreign investors, meaning some of these interest payments leak out of the U.S. economy. At a time when 15 percent of the population is living in poverty, leaks like this can’t be afforded.

Standard approaches to the problem involve some mix of spending cuts and revenue reform. If we’re spending more than we make, we need to spend less and make more — simple, right? But if Congress has taught us anything over the past few years, it’s that fiscal reform is apparently functionally impossible due to the deep political schism between Democrats and Republicans.

One approach that has been gaining more attention recently might be in a position to appeal to both sides of the aisle. If we make gross simplifications and assume that conservatives want to cut spending while liberals want to raise revenue, then the obvious middle ground is tax breaks.

You may have heard the horror stories already, but the U.S. tax code is monstrously large and complex. Buried within it are hundreds of tax breaks that have worked their way in over the years, often attached to unrelated legislation like some sort of fiscal parasite. These tax breaks reduce tax liabilities for big business, special interests, and for many individuals in one way or another. From the government’s point of view, a tax break is both lost revenue and a kind of spending.

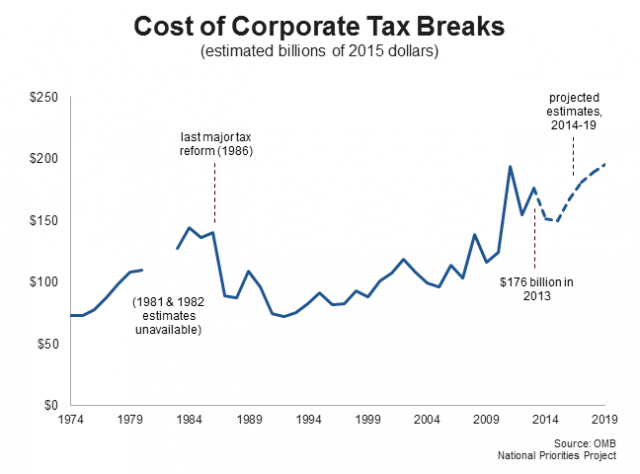

Removing tax breaks is a natural way to address a deficit, especially considering that may of the breaks on the books are going to businesses that really don’t need them. Research conducted by Citizens for Tax Justice showed that many profitable U.S. corporations pay little to no federal income taxes. Over a five-year observation period, CTJ calculated that 288 profitable corporations enjoyed tax subsidies worth $362 billion.

The icing on the cake here is that the cost of corporate tax breaks is expected to increase in the coming years. At a time when corporate profits are touching record highs, both in absolute terms and as a share of GDP, nearly every quarter, this trend is not right or reasonable.

Source: National Priorities Project

But here’s the true size of the tax break issue: According to the National Priorities Project, the total value of tax breaks in 2013 was $1.18 trillion, the same size as the government’s entire discretionary spending budget and 1.6 times the deficit. Most of these tax breaks, about $1 trillion, go to individual taxpayers and serve as a kind of fiscal stimulus, but as with most financial gains, the distribution of these tax breaks is highly unequal.

According to the CBO, 17 percent of individual tax breaks go to the top 1 percent of households. To rub salt in the wound, according to the Tax Policy Center, 4,000 of the taxpayers in the top 1 percent owed no income tax at all in 2013. The CBO estimates that 50 percent of total tax expenditures in 2013 went to the top income quintile, while just 8 percent went to the lowest income quintile. If that’s not some bullshit, we don’t know what is. Most tax expenditures are simply helping the wrong people.

But not all tax expenditures are created equal. While some, like reduced rates on capital gains taxes, almost exclusively affect those at the top of the income distribution, others, like the earned income tax credit, are designed to help those at the bottom.

“CBO estimates that more than 90 percent of the benefits of reduced tax rates on capital gains and dividends will accrue to households in the highest income quintile in 2013, with almost 70 percent going to households in the top percentile,” the group said. “Those benefits will equal 2 percent of after-tax income for the highest quintile and 5 percent of after-tax income for households in the top percentile. In contrast, about half of the benefits of the earned income tax credit will accrue to households in the lowest income quintile, equaling 6 percent of after-tax income for households in that group.”

So tax expenditures are not bad simply because they are tax expenditures, but the data suggest that tax breaks at large are being used poorly and to the detriment of the government, and through that, taxpayers. If policymakers want to make meaningful changes to fiscal policy, they will have to critically examine existing tax breaks and be cautious when designing new ones.