“Is the U.S. at War Right Now?" and Other Questions

By

Guest Blogger

Posted:

|

Military & Security

by Maryanne Magnier

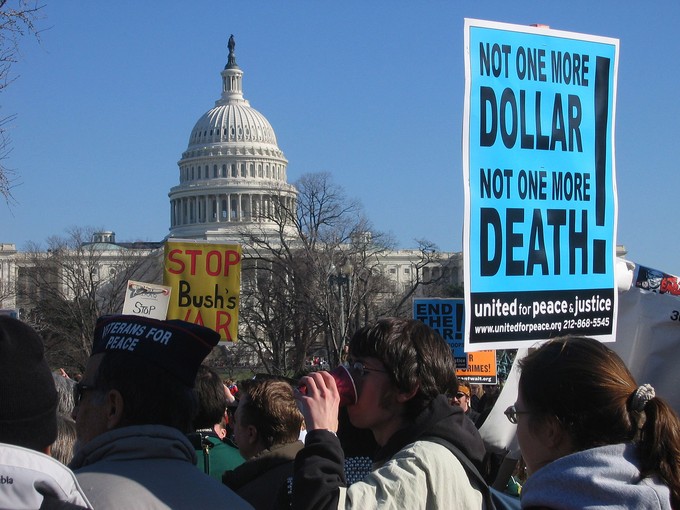

Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

Editor's note: At a time when the United States is in the midst of its longest war ever, with no end in sight; when the president routinely and offhandedly spouts threats of war; when the military budget is higher than at any time under President Ronald Reagan, and rising; and when the United States is engaged in a War on Terror in nearly half of the world's countries, the media and popular silence on issues of war and peace is deafening. Costs of War's Stephanie Savell recently wrote about her personal history of becoming an accidental anti-war advocate for TomDispatch. Here, NPP intern and Mount Holyoke College student Maryanne Magnier shares her personal perspective on why the anti-war movement doesn't resonate more with activist young people, and how it could.

“America may be more divided now than at any time since the Civil War.”

-Salon, 2017[1]

These bleak statements have been bandied about quite a bit since the election of President Trump last November. Perhaps I am more optimistic than the average person, but I disagree. I do not believe that people in this country have fundamentally changed in the past year or two. I do believe that everyone needs to come together and fight for the values the United States was founded on.

The United States was created as a safe haven for people to practice religious freedom. Yet Islamophobia is prevalent. The United States was built by immigrants. Yet our leaders are choosing to shut our doors to foreigners during a time of need. The United States has always been far from perfect, and a disconnect from these early values has always existed. Our Founding Fathers were emphasizing the importance of freedom while owning slaves in their own backyards.

We cannot pretend that we live in a country built on the bedrock of liberty and freedom when people are discriminated against every single day based on gender, race, religion, sexual orientation, et cetera. We need some sort of movement in this country to remove the disconnect between our theoretical values and how people are actually treated here.

Meanwhile, there has been aggressive war rhetoric sprouted about by our leaders recently, and in turn, talk of the need for a new anti-war movement has been increasingly relevant. The United States is now in its longest war ever. American troops have been in Iraq and Afghanistan for sixteen years with no end in sight.

It can be hard to picture what such a movement would look like. For a lot of people, war is an abstract concept. The coverage of foreign wars is typically given a backseat to the coverage of domestic politics. In one of my classes the other day, a fellow college student asked, “Is the U.S. at war right now? If so, with whom?” It is hard to rally around a cause that is not tangible or visible in the everyday lives of most, and it is impossible to rally around a cause you do not even know exists.

At the same time, the nature of warfare is changing. As emerging technologies such as drones make it easier to remove the human component of war, we will likely continue to see less boots on the ground and more eyes in the sky. It is hard to mobilize around a cause that is hard to see: out of sight, out of mind. All too often, we are unaware of drone strikes happening in faraway places. Since the United States can bomb countries without war being officially declared, the public is kept in the dark until after the fact. Drone strikes are often kept secret even once they are over.

And even for those of us with some awareness, there is a big difference between caring about an issue and actively participating in a movement. There is already so much going on, so many worthy causes. It is hard to choose what to fight for. My friends and I are all passionate and educated about a range of justice issues. However, most of the people I know have typically stuck to armchair activism, only attending protests on various issues (such as Black Lives Matter or the Women’s March) here and there. The last rally I attended was one on the National Mall a day or two after the deadly Charlottesville rally. It took a specific event for me to prioritize going out and protesting. But if a movement was more all-encompassing of several ideas I am passionate about, it would increase the likelihood of me getting involved.

The good news is that, like all movements, there are intersections. The anti-war movement does not stand alone. It is intertwined with feminism, Black Lives Matter, and Occupy. Movements that already have gained momentum are tied up in this fight. An example of a way the peace movement overlaps with issues that drive Black Lives Matter is a Department of Defense program where spare military equipment is given the police.

Then there’s the way the military disproportionately affects certain social groups. In “Who Joins the Military – A Look at Race, Class, and Immigration,” Amy Lutz shows how family income is an important predictor of military service. After conducting extensive research, she explicitly states, “Those with lower family income are more likely to serve in the military than those with higher family income. Thus the military may indeed be a career option for those for whom there are few better opportunities”.

This is one example of how different movements overlap with the anti-war movement. A lot of people choose to go into the military not to die in a blaze of glory, but to put food on the table. In the 2016 book “How Everything Became War and the Military Became Everything,” Rosa Brooks calls the military “a substitute welfare state… the last output of Big Government paternalism.” The military provides free healthcare to members and dependents, tax-free shopping, tuition assistance for spouse and children, discount groceries, subsidized child care, et cetera. Subsidized child care could be incentive enough for people, especially women, to stay in the military, seeing as the United States is one of only two countries in the world without guaranteeing paid maternity leave. (The second is Papua New Guinea, where 85% of the population relies on subsistence agriculture). Race and class are intertwined, so it is unsurprising that people of color are disproportionately represented in the military.

And there is a negative cycle here as well. As the military grows in size, it is more likely that its scope and jurisdiction expand. As Brooks says, it becomes a one-stop shop for a range of issues.

A main argument for not cutting the military budget is that over a million Americans rely on it for salary and benefits. There are ways to help people transition out of military careers, including severance packages and paid job trainings. But perhaps we should start with paid maternity leave and tuition that does not leave students in debt for decades. Maybe we should think about restructuring our economy so that military jobs don’t seem so indispensable. Perhaps we should continue these fights for greater justice and equality through the lens of an anti-war movement so that the military can stop being a welfare program, and instead become what it is most commonly understood to be: the way we go to war.

Maryanne is a student at Mount Holyoke College and a former Research Intern for National Priorities Project.