Yes, We Really Can Cut the Pentagon to Pay for Medicare for All

By

Lindsay Koshgarian

Posted:

|

Health Care,

Military & Security

Note: An earlier version of this blog incorrectly claimed that CRFB misidentified a key result of the PERI Medicare for All study. They did not. The below blog presents a corrected commentary.

Last night's debate, in which moderators asked whether spending on items like Medicare for All would lead to "bankrupting the country" while failing to ask any similar questions about the cost of two decades of war, has got me thinking again about the stories we hear (and don't hear) about the costs of various policy choices.

One form this takes is folks comparing the cost of Medicare for All to what we pay for the Pentagon. In one perfect example, a blog from Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget took issue with my October 17 op-ed in the The New York Times, “We Don’t Need to Raise Taxes to Have ‘Medicare for All.’” Their approach leaves out some of the most important considerations about what Medicare for All would cost, and their argument keeps being repeated, so it's worth a review.

The primary complaint from CRFB? That Medicare for All wouldn’t be fully covered by our suggested $350 billion in richly deserved Pentagon spending cuts, which we first wrote about in conjunction with the Poor People’s Campaign Moral Budget (and which I encourage folks to check out for their own sake, also to see that yes, the total really is $350 billion). CRFB is technically right (and so was I, in my Times op-ed), but CRFB's point isn't the full story.

Here’s whhat the CRFB analysis is missing:

1. $350 billion doesn’t need to cover Medicare for All. It just needs to cover the difference between Medicare for All and what we have now.

It’s entirely right that $350 billion is nowhere near the full cost of Medicare for All. But it doesn’t need to be.

We made this clear in the Times op-ed: that we found the “$300 billion per year over the current system that is estimated to cover Medicare for All (though estimates vary).” (Emphasis added.)

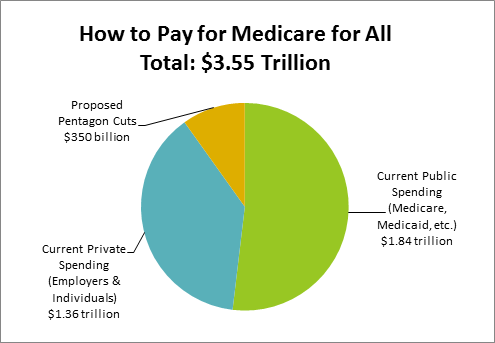

In 2017, we (collectively, public and private) spent $3.2 trillion on health care. The $350 billion we identified in Pentagon budget cuts only needs to cover the difference between what we pay now and what Medicare for All would cost. The $3.2 trillion we spend now could be redirected to Medicare for All, albeit with serious questions about how to make sure the cost is borne fairly. Together, our current spending of $3.2 trillion, plus the $350 billion in Pentagon cuts, would be more than enough to pay for Medicare for All.

And, it turns out that CRFB knows this, as they acknowledge in the sixth paragraph.

How to Pay for Medicare for All (in part) by Cutting the Pentagon

Sources: PERI, National Priorities Project

CRFB aren’t the only ones to use this misleading reasoning, but it just doesn’t check out. More than half of the $3.2 trillion in current health care spending is already flowing through the federal government, as part of Medicare and Medicaid and other public systems. Sure, most Medicare for All proposals involve shifting the cost burden for health care around to some degree, but the argument shouldn’t be about whether the money is there – it definitely is, because we're already spending it. That’s why we can talk about the $300 billion in additional funding without belaboring the full cost of Medicare for All.

And for anyone concerned about the deficit, the fact that Medicare for All could in fact cost less overall than the current system should matter. A lot. Less money wasted on health care profits and bloated insurance bureacracies means more for everything else, including potential federal revenues.

2. We are already spending outrageous amounts on health care.

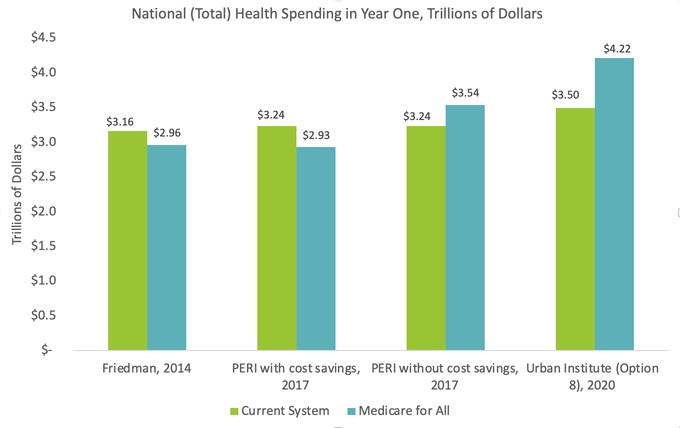

The chart below shows total health spending - also known as national health spending (versus federal spending) estimated by three studies that look at both the federal portion and overall spending on health care.

This matters because one of the biggest problems with the current system - aside from how many people remain uninsured or have inadequate health insurance - is how expensive it is. The U.S. spends far more per person on health care than the rest of the developed world - mostly because of the higher prices we pay. Medicare for All has the potential to significantly cut those prices, and could either reduce or limit total costs even while it insures more people.

The main PERI estimate - and the figures most commonly cited - depend on PERI's relatively aggressive cost savings estimates, and would put national health spending at $2.93 trillion in 2017.

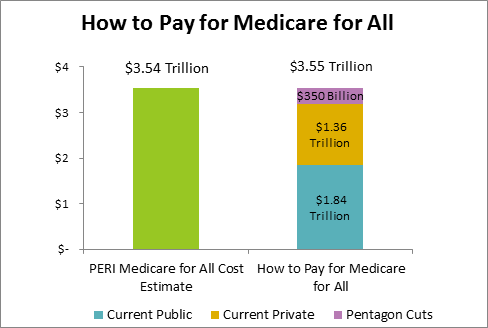

But, the PERI estimates we used to suggest partially paying for Medicare for All by cutting the Pentagon don't figure in any cost savings and are based only on PERI's estimate of the increased cost of fully covering everyone (both the uninsured and the underinsured) under Medicare for All. The estimate we used finds national health spending of $3.54 trillion.

By comparison, Friedman found approximately the same national health spending - and probably slightly higher, especially given the difference in base year - of $2.96 trillion, also with substantial cost savings. The Friedman estimate is $580 billion lower than the PERI estimate without cost savings ($3.54 trillion). The Urban Institute study found national health spending of $4.22 trillion under the most expansive version of Medicare for All.

So, Friedman and the main PERI estimate show national health costs being reduced under Medicare for All, while the non-cost-saving PERI estimate and the Urban Institute estimate find national health costs increasing. For reference, each study's estimate of national health spending under the current system in the given year is shown below.

Sources: Friedman, PERI, Urban Institute. This chart is a corrected version of one posted previously.

CRFB and other analysts are often more concerned with the federal portion of health spending than with the system overall. The federal portion of Medicare for All no doubt matters, but it's not the full story. People care about whether their health care is affordable, and that includes the entire amount they pay, not just whatever they may pay in federal taxes.

3. Medicare for All Could Cost Less Than the Current System

While estimates vary, the reality of Medicare for All could actually save money compared to the current system, if deeper cost savings were achieved. PERI estimates that by implementing cost saving measures like prescription drug price controls, limits on hospital profits and reducing administrative overhead, the total cost of Medicare for All could be as low as $2.93 trillion in the first year, which would return $310 billion for other uses compared to the current system. Other studies suggest lower savings, and some suggest that those savings would be less than the increase in costs. The chart below shows the cost, and a possible payment scheme, for Medicare for All using the more pessimistic PERI estimates.

The Urban Institute has a more pessimistic view of cost growth and savings, and estimates that Medicare for All would cost about $700 billion per year more than the current system. Even then, our Pentagon cuts could cover roughly half of the increased cost of Medicare for All - a significant portion.

With nearly 28 million Americans uninsured, an additional 29 percent of insured Americans having inadequate coverage, and wildly growing health care costs, we can't afford to continue on the current path. And we can't ignore the lesson of the rest of the developed world, showing us that the high price we pay for health care isn't a necessity - it's a choice.

Our suggested Pentagon cuts aren't the full solution to our health care problems, but they are worthwhile for two reasons: first, because those revenues could be put to use on desperately needed reforms to health care, or clean energy, or any number of things. And second - and having nothing to do with Medicare for All - because the cuts we propose would make us safer.

Sources: PERI, National Priorities Project