The Untold Story of Deficits in Washington

July 19, 2012 - Download PDF Version

By Mattea Kramer

Research Support by Andrew Fieldhouse

** UPDATE **: View Where's the Revenue? Infographic

Tax revenues have plummeted. And the reason isn’t just the recession.

In 2000, the federal government had a balanced budget and projected surpluses for years to come. Fast forward a decade, and Washington runs steep budget deficits while news media report that federal spending is out of control. Americans now list federal debt and deficits as one of their top concerns for the nation.[1] But deficits depend on two things: spending and revenue. In 2000, when the budget was balanced, federal tax revenue amounted to around 20 percent of the U.S. economy.[2]

Why measure tax revenue as “a share of the economy”?

The U.S. economy in 2012 is different than it was in 2000. In order to compare tax revenue across years, we measure revenue as a percentage of Gross Domestic Product (GDP), the size of the overall economy.

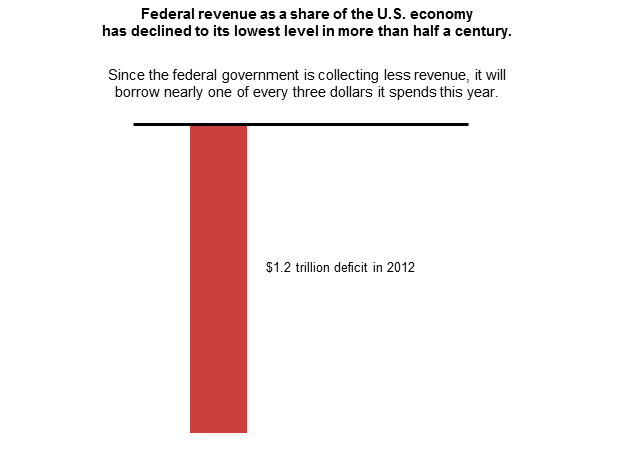

Federal revenue as a share of the economy has dropped sharply since then, to its lowest point in more than half a century.[3] Federal spending has increased in recent years, and this rise in spending has received ample coverage in the news media. Some lawmakers say the only solution to deficits is to make deep cuts in federal programs.

Yet there has been little mention of dwindling revenue.

What caused the decline in tax revenue?

Federal revenue has declined over the last decade as a result of a host of tax cuts and growing exploitation of deductions, credits, and loopholes. Tax cuts in 2001 and 2003 helped turn budget surpluses into deficits, and the federal government has now run deficits for over a decade. The deficit in fiscal year 2012 is projected at $1.2 trillion,[4] which means the federal government will borrow nearly a third of every dollar it spends this year.[5]

The Great Recession has also contributed to the federal government’s cash shortfall – when fewer people are employed, fewer people pay taxes. But even without the weak economy, the federal deficit would be sizeable.[6]

Here’s how the budget deficit would change if lawmakers ended tax cuts or closed credits and deductions:

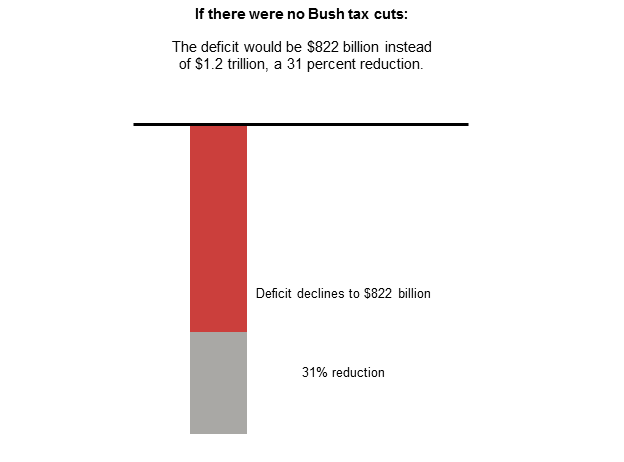

If there were no Bush-era tax cuts

Nearly a third of the budget deficit in fiscal 2012 would disappear if there had been no Bush tax cuts, as the federal government would raise an additional $305 billion in revenues and spend $68 billion less on interest payments for borrowed funds.[7] Of these savings, $97 billion would result from additional taxes paid by the top 1 percent of Americans, while $244 billion would come from extra taxes paid by the top 20 percent.[8]

Most Americans would pay higher taxes if the Bush-era tax cuts were not in effect. Since lawmakers in general do not want to raise taxes for middle-class or low-income Americans, some members of Congress have proposed ending tax cuts only for upper-income taxpayers. In 2012, the average taxpayer in the top 1 percent will receive a tax break of $70,250 as a result of Bush-era tax cuts.[9] That tax break is larger than the average income for the other 99 percent of Americans.

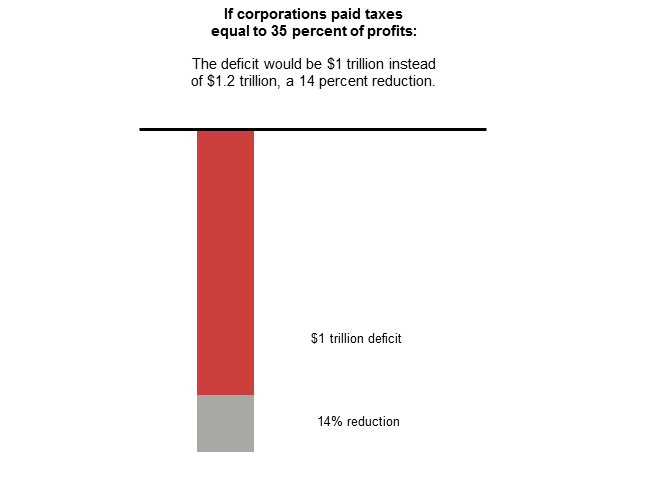

If corporations paid the official corporate tax rate

If corporations paid the top official tax rate of 35 percent on all profits, the federal government would raise an additional $165 billion in tax revenue this year.[10]

Thirty-five percent is the official tax rate for corporate income in excess of $18 million, though many corporations don’t pay that rate. According to the Congressional Budget Office, corporate income taxes totaled $181 billion in fiscal 2011, or around 9.5 percent of all corporate profits.[11] And over the last three years, corporate income taxes have averaged 1.2 percent of GDP – that’s the lowest level in half a century.[12]

Corporations often pay a tax rate lower than 35 percent due to credits and deductions, and because profits attributed to corporations’ overseas operations are often not taxed by the U.S. government.

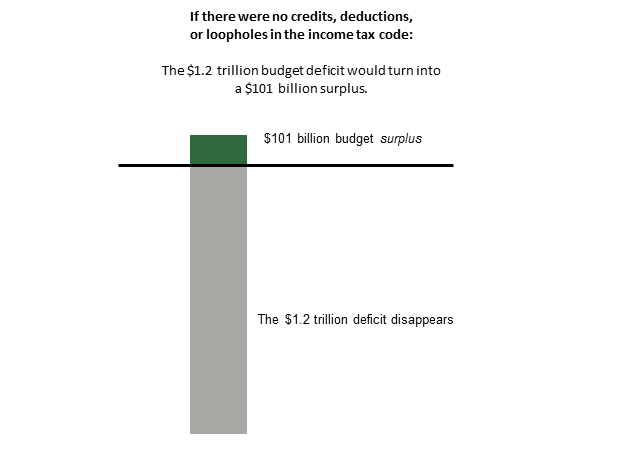

If there were no credits, deductions, or loopholes in the income tax code

Without the hundreds of credits, deductions, and exclusions in the individual and corporate income tax codes, the federal government would raise an additional $1.3 trillion in tax revenue in 2012.[13] The budget deficit would disappear, and the federal government would run a surplus. Closing all those credits and deductions would mean taxing capital gains and dividends like ordinary income, taxing employer contributions to employee health care, and closing roughly 200 other credits, deductions, and exclusions that affect corporate and individual taxpayers.

If lawmakers closed all credits and deductions, most corporations and most Americans would pay more tax. Since lawmakers in general do not support raising taxes for middle-class or low-income Americans, some lawmakers have proposed modifications that would only affect wealthy Americans.

For example, the home-mortgage interest deduction gives wealthy taxpayers a tax break for purchasing second and third homes. Even a yacht can be classified as a home for the purpose of tax benefits. In 2011, the home-mortgage interest deduction handed a $4.4 billion housing subsidy to the top 1 percent of taxpayers.[14] Many other provisions in the tax code – such as the special low tax rate for capital gains – disproportionately benefit wealthy taxpayers. Changes to these provisions could bring in many billions of dollars in additional tax revenue without raising taxes for middle-class or low-income Americans.

But Wait… Deficits Also Serve a Purpose

Just because lawmakers could eliminate the entire budget deficit with these changes to the tax code doesn’t mean they should immediately do so.

That’s because deficit spending serves a purpose in a weak economy. Most economists think the federal government should help a fragile economy either by spending more – for example, on unemployment benefits or infrastructure improvements – or by reducing taxes. That makes deficit spending an important part of the federal government’s response to a recession.

Federal spending will automatically decline in a stronger economy as fewer people qualify for unemployment benefits, food stamps, and other safety-net programs, and tax revenues will increase as more Americans find jobs. But that won’t be enough to close deficits. Lawmakers can increase tax revenues by closing credits and deductions in the corporate and individual income tax codes, ending the Bush-era tax cuts, or making other changes to tax policy – and thereby reduce budget deficits.

[1] Gallup, “U.S. Voters Top Election Issues…”

[4] Congressional Budget Office, March 2012 Baseline

[5] Congressional Budget Office, March 2012 Baseline

[6] Economic Policy Institute, “Big recession, big deficits”

[7] Citizens for Tax Justice. Revenue figure includes outlay effects associated with the Bush-era tax cuts.

[10] Calculation reflects 35% of CBO’s projected FY12 corporate profits with inventory valuation adjustment and capital consumption adjustment, less income from Federal Reserve Banks and net income received from equities in foreign corporations (calculated as a share of projected profits by the chained dollar weighted share of net foreign equity income over 2003-2008). Projected corporate income receipts under the alternative fiscal scenario (i.e., adjusted for continuation of the business tax extenders) are netted out of this revenue figure, as are S-corporation individual income taxes, excluding capital gains (calculated from Tax Policy Center Table T11-0154, adjusted from 2011 to fiscal 2012 with projected growth in corporate profits). Dividends and capital gains tax receipts from S-corporation are also netted out, calculated as 40% of capital gains and dividends receipts (the share from pass-throughs in 2007) weighted by S-corporation income as a share of total pass-through income. Lastly, this net decrease in corporate profitability is adjusted for contemporaneously decreased dividends disbursements and capital gains realizations, using the statutory 15% tax rate and the rule of thumb that roughly half of capital gains realizations and half of dividends are not taxed a second time at the individual income level (for an effective net-of-tax rate of 92.5%). See http://www.cbo.gov/sites/default/files/cbofiles/attachments/Jan2012_EconomicBaseline_Release.xls; http://www.taxpolicycenter.org/numbers/displayatab.cfm?DocID=3035; http://www.irs.gov/pub/irs-soi/10winbulcapitalassets.pdf; http://www.taxpolicycenter.org/UploadedPDF/1000460_dividend.pdf; and Bureau of Economic Analysis National Income and Product Accounts Tables 6.16.D, 7.16, 1.1.4, and 3.2.

[11] Congressional Budget Office, Fiscal and Economic Outlook 2012-2022

[13] Tax Policy Center, “How Large Are Tax Expenditures?”

[14] Tax Policy Center, “Tax Benefits of the Mortgage Interest Deduction”