What Is Entitlement Reform?

By

Mattea Kramer

Posted:

|

Health Care,

Social Insurance, Earned Benefits, & Safety Net

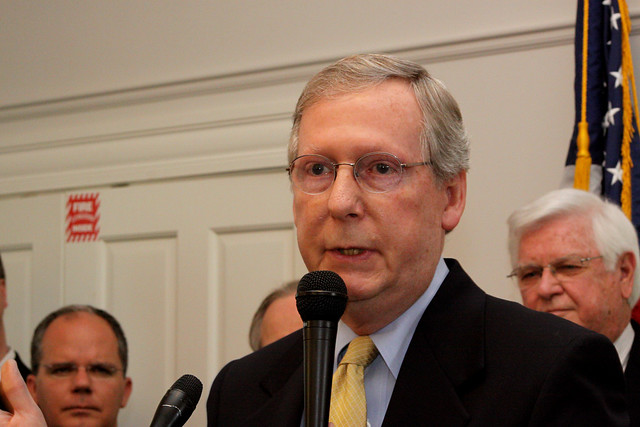

Sen. Mitch McConnell (R-Ky.) has said further deficit reduction must come from health care programs

Photo by Gage Skidmore/ flickr

When lawmakers struck a fiscal cliff deal on New Year's Day, they did not make any changes to Medicare or Social Security. But the debate over if and how to reform entitlement programs has only just begun.

To understand this issue, we should define a couple key terms. First, entitlement programs have their name because eligible Americans by law are entitled to benefits from Medicare, Social Security, and a handful of other programs in this category. Entitlement reform refers to the proposal by some lawmakers that such programs should be overhauled in order to reduce spending.

Indeed, entitlement reform is attracting attention right now because entitlement programs like Medicare and Social Security take up a large share of the federal budget, and they're getting more expensive over time. The cost of health programs in particular is projected to rise steeply in the coming years, even as health care already has risen from 7 percent of the federal budget in 1976 to around a quarter of the entire budget this year.

So, what kinds of reforms are lawmakers proposing? Two major changes to entitlement programs were considered during negotiations over the so-called fiscal cliff.

Entitlement Reform and Medicare

Some lawmakers proposed gradually raising the Medicare eligibility age from 65 years old to 67, and this received substantial criticism. The Wall Street Journal reported that doing so would raise health care costs considerably for the people affected or their employers, but it wouldn't necessarily create great savings for the federal government since it would increase federal spending for the Medicaid program even as it reduced spending for Medicare.

Entitlement Reform and Social Security

The second proposal concerned Social Security. Some lawmakers suggested changing the way cost-of-living adjustments are made to Social Security benefits; cost-of-living adjustments are gradual increases in benefits that are meant to ensure that retired and disabled people see their Social Security checks grow with the pace of inflation. The proposal considered last month would slow those cost-of-living adjustments by modifying the way inflation is calculated; that would lead to an erosion in the value of Social Security benefits over time. Doing so would reduce federal spending on the program, but critics of the proposal pointed out that it was essentially just a benefit cut, since the alternate measure of inflation would not be a more accurate gauge of living costs for Social Security beneficiaries.

Looking Ahead

There are many other reform proposals that were not considered in December but may gain attention in the coming months. Some experts would like to introduce something called graduated eligibility into both Medicare and Social Security; that would delay Medicare and Social Security eligibility only for wealthy individuals, while there would be no changes to eligibility rules for lower-income Americans. Another proposal that may be tossed around would affect only Social Security. Currently workers pay Social Security taxes on their first $113,700 in wage income, and then nothing after that. Raising that maximum would bring in additional revenue for the program.

And in the coming months there will likely be a flurry of other proposals for how to reform entitlement programs or control health care costs.