Budget Process

Federal Budget 101

What sort of country do you want to live in?

Do you want access to education? Health care? Clean energy? Job opportunities? How much are those things worth?

Does it make sense that the richest country in the world still has rampant poverty?

How did we end up with policies that nurtured white supremacy, mass incarceration and police violence, and what can we do to stop them?

Should we deport community members who don’t have immigration papers, or welcome them?

When is war justified?

Every one of today’s hot button issues can be found in the federal budget. How much we spend on education versus war, or health care versus incarceration, shows our values as a nation. Those values may be very different from yours.

There have always been people who disagreed with our national budget priorities. History is full of examples of ordinary people working together to end wars, expand health care, win civil rights, and so much more. That story continues today, and you are a part of it.

How It’s Supposed to Work (and How It Does)

The U.S. Constitution promises the "power of the purse,” or the ability to spend money, to Congress.1 This part of the Constitution doesn’t even mention the president. The constitution also grants Congress the authority to create and collect taxes, and to borrow money when needed. The Constitution does not, however, specify how Congress should exercise these powers, how to spend or raise money, or where the money should go.

In 1974, in response to a dysfunctional budget process, Congress passed a law setting some guidelines for how to create the federal budget. Over the course of the twentieth century, Congress passed laws that have shaped the budget process into what it is today. Unfortunately, the budget process today is still rife with dysfunction – and yet, every year, Congress passes a budget. We’ll tell you how it works.

The Annual Budget Process – What’s In and What’s Out

The federal budget is made up of two major kinds of spending: mandatory and discretionary spending. A third category, interest on the national debt, will come up later.

To set the federal budget, Congress passes two kinds of laws that set the budget for our country. The first are called authorization. These are necessary for both mandatory and discretionary spending. There are also appropriations, which legislate what is known as discretionary spending. The way issues end up in one bucket or the other has a lot to do with history.

Authorizations bills3 for mandatory spending often last several years. When a spending authorization finally expires, Congress can vote to continue it as is, or make changes. Congress can also make changes along the way, but if they don’t, this spending continues pretty much on auto-pilot.

The biggest and most well-known examples of mandatory spending are Social Security, Medicare and Medicaid benefits. In these programs, how much is spent depends on how many people qualify. If lots of people retire and qualify for Social Security checks, more is spent. If fewer people retire, less is spent. Everyone who is eligible can get benefits.

Then there are appropriations bills, which focus on discretionary spending. Appropriations last just one year, and do set a specific budget. If that money runs out before the end of the year, the government can’t spend more unless Congress votes on a new appropriation. Then, Congress does it all again next year.

The biggest example of discretionary spending is the military budget, which accounts for half or more of the discretionary budget almost every year (the COVID-19 pandemic is a recent exception). The other half is split between things like public education, housing, public health, medical research, energy, the environment, federal law enforcement, and even veterans’ benefits, which aren’t part of the military budget. Most federal programs, and possibly most issues you care about, have to squeeze into this part of the federal budget.

The Annual Budget Process

The U.S. federal budget operates on fiscal years that run from October 1 to September 30. For example, FY 2021 ran from October 1, 2020 through September 30, 2021. Each year, Congress sets discretionary spending levels through the appropriations process, with the President playing a supporting role.

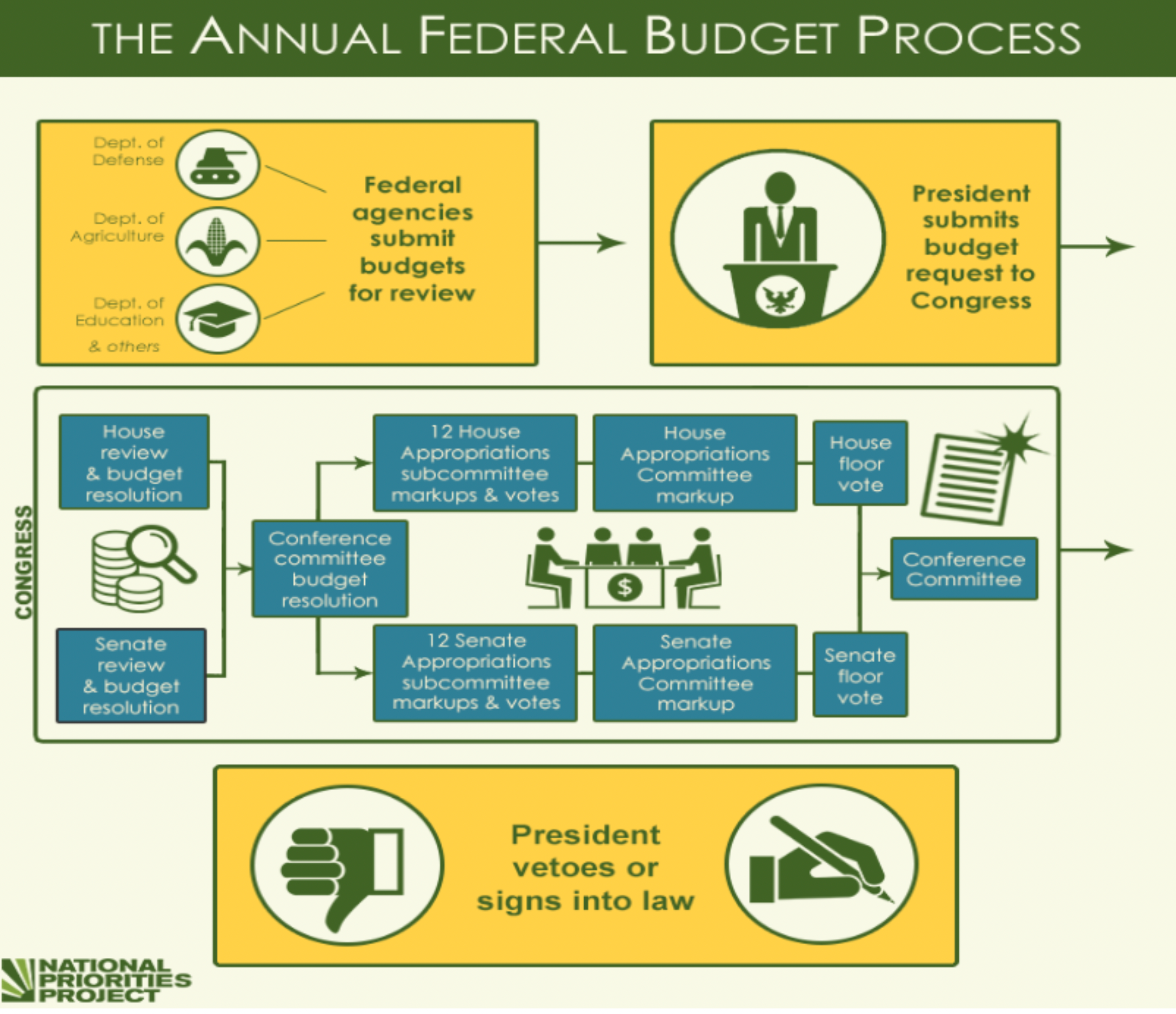

This is how the appropriations process is supposed to go:

- The President submits a budget request to Congress for what he/she/they would like to see.

- The House and Senate pass budget resolutions, setting total spending levels for the year. They may or may not take the President’s recommendations.

- House and Senate Appropriations committees put together 12 detailed appropriations bills representing 12 separate areas of government. This process takes a while.

- The House and Senate each vote on the 12 appropriations bills and iron out their differences.

- The President signs each of the 12 appropriations bill. Now the budget is law.

Step 1: The President Submits a Budget Request

According to federal law, the president should budget request to Congress each February for the coming fiscal year.5

To start, each federal agency works with the Office of Management and Budget, which is part of the White House. The budget requests describe what the leaders of each government agency think they need to run things for the current year.

The Office of Management and Budgets works with agencies to combine these budgets into the president’s budget request. The president’s request also includes the president’s preferred tax policies and how the government will bring in money.

But the president's budget request is just a suggestion. Congress then writes its own appropriations bills, which may have little in common with the president’s request. The president’s power over the budget comes largely from the ability to veto appropriations bills passed by Congress. Only after the president signs these bills (in step five) does the country have a budget for the new fiscal year.6

Step 2: The House and Senate Pass Budget Resolutions

After the president submits his or her budget request, the House Committee on the Budget and the Senate Committee on the Budget each write and vote on their own budget resolutions.7

The budget resolution sets the year’s spending limits for the 12 main areas of federal discretionary spending. It also includes estimates for how much money will be brought in through taxes and other means. The budget resolutions from the House and Senate don’t get into much detail or set funding for individual programs. That happens later.

The House and Senate each pass their own budget resolutions. Then, members from each come together in a joint conference to iron out differences between the two versions – sometimes a very difficult and contentious process. If they can agree on a compromise version, the resulting “reconciled” version is then voted on again and must pass in each chamber.

Sometimes, Congress fails to pass a budget resolution setting spending limits – either because the Senate or House (or both) fail to pass one, or because the Senate and House can’t agree on a “reconciled” version. When that happens, it can make the rest of the process longer and more difficult.

Step 3: House and Senate Create Appropriation Bills

The House and Senate both have Appropriations Committees that are made up of members of Congress. These committees are responsible for determining the precise levels of budget authority, or allowed discretionary spending, for all discretionary programs in the federal budget.8

The Appropriations Committees in both the House and Senate are broken down into 12 smaller appropriations subcommittees. Each of these are responsible for creating an appropriations bill. Subcommittees cover different areas of the federal government: for example, there is a subcommittee for military spending, and another one for energy and water. Each subcommittee conducts hearings in which they seek additional information about how they should fund government agencies and programs.9

Based on all of this information, the chair of each subcommittee writes a first draft of the subcommittee's appropriations bill, abiding by the spending limits set out in the budget resolution, if there was one. All subcommittee members then get chances to change the bill and vote on it. Once they pass in their subcommittees, each of the 12 bills goes to the full Appropriations Committee. The larger committee can then change it even more, and vote to send it to the full House or Senate for a final vote. In recent years, the House and Senate have not followed this process. Instead of working on 12 distinct appropriations bills, they have put all federal discretionary spending into one big appropriations bill known as an omnibus. This can result in rushed passage of a bill too big and complicated for anyone to even read – both concerned citizens, and even members of Congress themselves.

Step 4: The House and Senate Vote on Appropriations Bills

After the committee votes, all 435 members of the House of Representatives and 100 members of the Senate get a chance to vote on the 12 appropriations bills.

After the House and Senate pass their versions of each appropriations bill, a conference committee meets to iron out any differences between the House and Senate versions – just like they did for the budget resolutions. After the conference committee produces a single “reconciled” version of the bill, the House and Senate vote again, but this time on a bill that is identical. After passing both the House and Senate, each appropriations bill goes to the president for his or her signature.10

In reality, the budget process can (and often does) get stuck at any of the points along the way so far.

Step 5: The President Signs Each Appropriations Bill and the Budget Becomes Law

The president must sign each appropriations bill after it has passed Congress for the bill to become law. When the president has signed all 12 appropriations bills, the budget process is complete. Rarely, however, is work finished on all 12 bills by Oct. 1, the start of the new fiscal year.

This chart shows how all of these pieces fit together to make the annual federal budget process.

Continuing Resolutions and Omnibus Bills

When the budget process is not complete by Oct. 1, Congress may pass a continuing resolution so that agencies continue to receive funding until the full budget is in place.11.

If Congress does not pass appropriations or a continuing resolution by October 1, the government won’t have money to function. That results in a shutdown of the federal government, in which many parts of the government stop operating. This has happened many times over the years.

Supplemental Appropriations

From time to time the government has to respond to emergencies, such as the COVID-19 pandemic, natural disasters, or overseas conflicts. In these cases, the government may need to appropriate more spending to handle the crisis. This type of funding is allocated through legislation known as supplemental appropriations.

It's Even Messier than It Sounds

The process above is the way the federal budget is supposed to be made, but it rarely goes according to plan. But regardless of how the process goes, there are always points where people in this country can weigh in to let their representatives know what they want, and don’t want, in the federal budget.

Endnotes

- U.S. Constitution, article 1, section 8, clause 1.

- Congressional Research Service, "Introduction to the Federal Budget Process," Report 98-721, 3 Dec. 2012.

- Congressional Research Service, "Overview of the Authorization-Appropriations Process," Report 20-731, 26 Nov. 2012.

- Congressional Research Service, "Mandatory Spending: Evolution and Growth Since 1962," Report 33-074, 10 Mar. 2014.

- Congressional Research Service, "Introduction to the Federal Budget Process," Report 98-721, 3 Dec. 2012.

- U.S. Constitution, article 1, section 7, clause 2.

- Congressional Research Service, "The Congressional Budget Process: A Brief Overview," Report 20-095, 22 Aug. 2011.

- Congressional Research Service, "The Congressional Budget Process: A Brief Overview," Report 20-095, 22 Aug. 2011.

- Congressional Research Service, "The Congressional Appropriations Process: An Introduction," Report 42388, 14 Nov. 2014.

- Congressional Research Service, "The Congressional Budget Process: A Brief Overview," Report 20-095, 22 Aug. 2011.

- Congressional Research Service, "Continuing Resolutions: Overview of Components and Recent Practices," Report 42647, 14 Jan. 2016.